With the re-election of President Donald Trump, the worries about tariffs and pro-business policies sparked concerns of “Trumpflation.” Inflation has been a top concern for policymakers, businesses, and everyday consumers, especially following the sharp price increases experienced over the past few years.

However, growing evidence shows inflationary pressures continue to ease significantly, paving the way for lower interest rates. The question is whether policies being considered by the next Presidential administration will lead to “Trumpflation” or not.

Current Thinking

Many mainstream economists and analysts believe President Trump’s economic policies could trigger “Trumpflation.” The term refers to potential inflation driven by his administration’s fiscal and trade policies. Analysts suggest that extending the TCJA tax cuts, further tax cuts, infrastructure spending, or increased military budgets will boost economic growth and lift inflation. The belief is that this fiscal stimulus, especially during an already low unemployment environment, would increase demand, leading to price increases.

Furthermore, “Trumpflation” could be triggered by introducing trade protectionism and tariffs. Economists argue that restricting imports and raising tariffs on foreign goods will lead to higher domestic prices, as the costs of imported goods would rise. Combined, these policies pointed to risks of higher consumer prices and potentially higher interest rates.

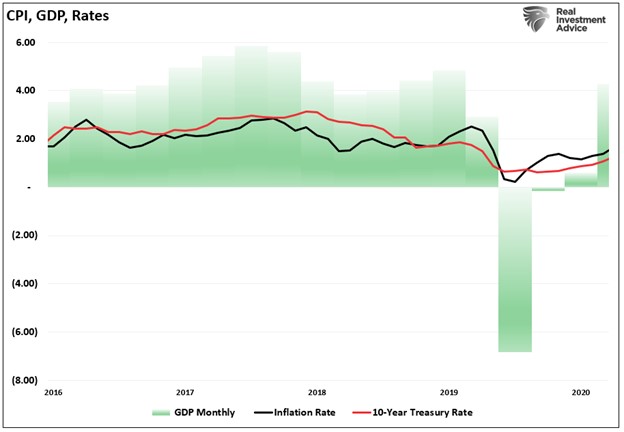

The advantage that we have today is that we can review President Trump’s first term to see if the same policies instituted then led to higher interest rates and inflation. Following his election in 2016, he instituted tariffs on China, cut taxes, and passed regulations that preceded less immigration and increased business investment. The chart below shows his first term’s economic growth, inflation, and interest rates. (Note: The chart below begins on November 1, 2016, and ends on January 20th, when President Biden took office.

What is crucial to note is that while his policies led to more robust nominal economic growth (as measured by GDP), inflation and interest rates remained range-bound to roughly 2%. That is until the pandemic arrived in early 2020, which led to a collapse in both rates and inflation.

We Have Been Here Before

While many predict “surging inflation” resulting from President Trump’s plans for tariffs and increased deficit spending, a historical review for perspective is valuable. Let’s start with tariffs.

As noted above, Trump instituted tariffs in 2016 without an impact on inflation. However, a 2015 paper by the Tax Foundation gives us some additional perspective:

“Let’s travel back one hundred years to 1915. Back then, the main sources of federal revenue were very different. Almost half of all federal revenue came from excise taxes, such as taxes on liquor and tobacco. Another 30.1 percent of federal revenue came from customs duties, or tariffs, on imported foreign goods.“

In other words, 80% of all tax revenue came from excise taxes and tariffs, while individual and corporate taxes were about 6% each. That lasted until Congress passed the Revenue Act in 1942, which reduced tariffs and increased personal and corporate income taxes.

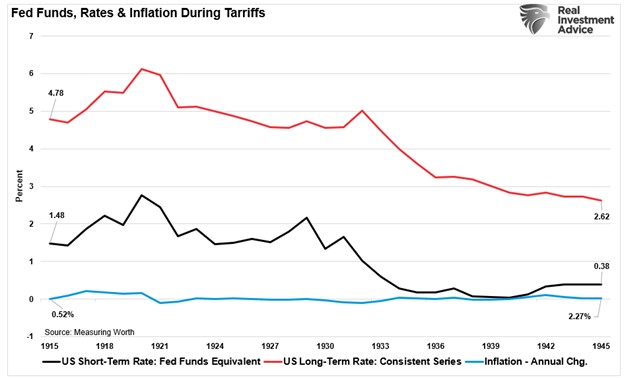

Given economists’ current concern that “Trumpflation” is returning, the historical evidence of previous tariff usage does not corroborate those concerns. The chart below shows the Federal Funds rate equivalent, the 10-year Treasury rate, and the annual change in inflation from 1915 to 1945. (Note: The U.S. economy was in a depression starting in 1933, accelerating the interest rate decline.)

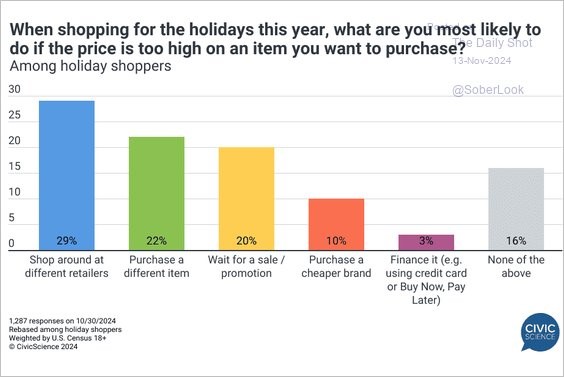

The current economic environment is very different from the early 20th century, which we will address momentarily. However, today, globalization and technology give consumers vast choices in the products they buy. While instituting a tariff on a set of products from China may indeed raise the prices of those specific products, consumers have easy choices for substitution. A recent survey by Civic Science showed an excellent example of why tariffs won’t increase prices (always a function of supply and demand).

Of course, if demand drops for products with tariffs, prices will fall, reducing inflationary pressures.

However, another fallacy is that tariffs will increase inflation due to increased domestic production, leading to higher wages.

The Negative Side of Productivity

In early December 2016, I discussed that “Trumpflation” would not likely occur due to the ongoing decline in manufacturing and increases in productivity efficiencies. Those efficiencies will be amplified by “Artificial Intelligence.” However, while tariffs may bring manufacturing back to the U.S., it just won’t be in the manner that most economists expect.

“In any event, the horses may already be out of the barn. Only 8.5% of payroll employment is now attributable to manufacturing, down from 10.3% 10 years ago, 14.3% 20 years ago, and 17.5% 30 years ago. Bringing factory jobs back to the US may bring them back to automated factories loaded with robots. Even Chinese factories are using more robots.” – Dr. Ed Yardeni.

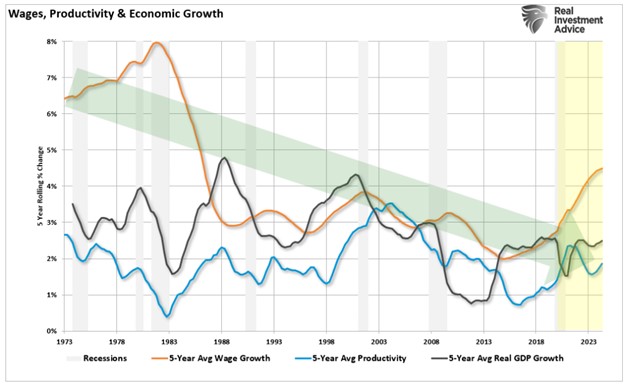

In 2024, manufacturing comprises just 20% of the economy, while services dominate the other 80%. This is crucial to the expectation of inflationary outcomes. Manufacturing has a high multiplier for each dollar spent, whereas services do not. Furthermore, service jobs have lower wages than manufacturing jobs, which depresses economic growth. Starting in 1980, as the economy transitioned, the 5-year average growth rates have slowed outside of the artificially induced pandemic-related surge.

As noted in that 2016 article, productivity is the key to whether or not “Trumpflation” becomes a risk.

“Slow productivity growth is the leading cause of slow economic growth, and slow economic growth makes it all but impossible for everyone’s boat to rise. No wonder angry citizens want dramatic change. But while voters may see the problem in a political establishment that is out of touch, the populist politicians who are challenging that establishment are unlikely to fare better.

In the short term, they may be able to medicate the economy with a big tax cut or a dose of deficit spending. When the effects of that treatment wear off, though, the effects of slow productivity growth will linger.” – Harvard Business Review

In 2025, as Trump takes office, the impacts of his policies will still be mitigated by the existing “3-D’s:” Demographics, Deflation, and Debt.

Debts & Deficits Are a Problem, Just Not an Inflationary One

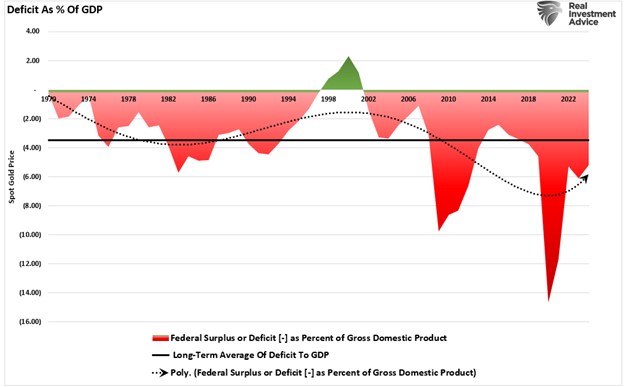

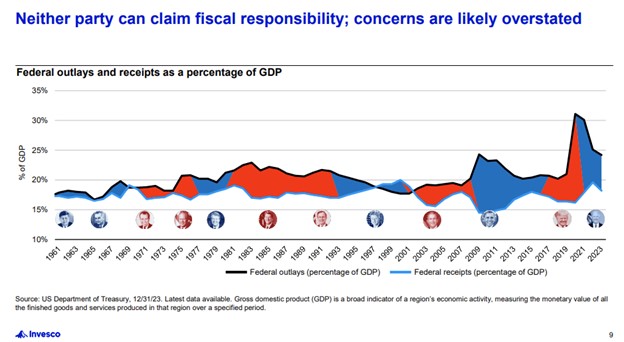

Beyond the productivity problem are debt and deficits, a repeated concern of bond bears, deficit hawks, gold sellers, and those “fear-mongering” over the upcoming Trump presidency. However, neither party can claim fiscal responsibility. The concerns over the deficit and the debt remain overstated.

First, the deficit can not be viewed in isolation and must be compared to economic growth. Since the 2020 monetary spending spree, the deficit has reduced substantially as a percentage of GDP. This is because both spending levels have declined while economic growth has rebounded sharply.

Furthermore, while much of the media wants to accuse President Trump even before he takes office by suggesting he will massively increase the deficit and spending, neither party can claim any “fiscal” responsibility.

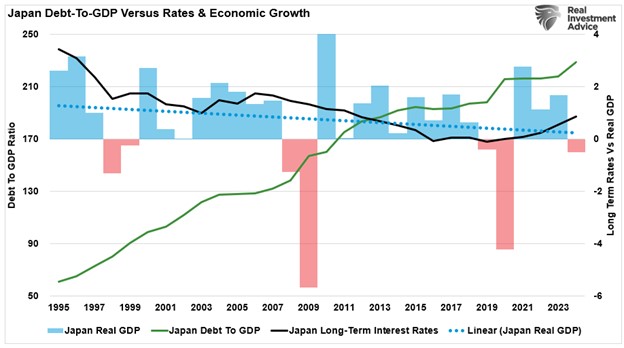

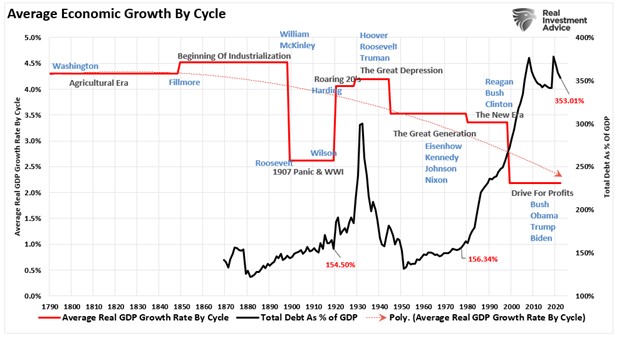

While government debt and deficits are concerning, they are not “inflationary.” As noted above, “Debt” is one of the precursors of “deflation.” Again, historical evidence supports that claim, particularly when slowing demographics are combined with massive debt burdens. This past week, we discussed Paul Tudor Jones’s misunderstanding of these issues.

“As shown, the experience of Japan provides further evidence that high debt levels do not lead to runaway inflation or surging interest rates. Despite carrying a debt burden pushing 250% of GDP, Japan has faced persistent deflation and falling interest rates for the past three decades. This is largely due to weak demand and an aging population, factors that have suppressed inflationary pressures despite aggressive monetary easing,”

As we concluded in that analysis:

“Rising government debt has not correlated with higher interest rates (or inflation) over the past few decades. Since 1980, total U.S. debt as a share of GDP surged from 156% to nearly 353%, yet economic growth and interest rates slowed during that period. Despite increasing debt, the persistence of low rates and slower economic growth reflects the diversion of productive capital into non-productive debt service. In other words, debt is “deflationary” as it retards economic prosperity.”

Beyond these primary factors, there are several other reasons why “Trumpflation” will likely not manifest as expected.

Headwinds to Trumpflation

Most of the fears of “Trumplation” are derived from the recent inflation spike following the pandemic. However, that inflation was artificially created by shutting down production while increasing demand through one-time stimulus payments. Moving forward, there are four reasons why another surge in inflation is unlikely.

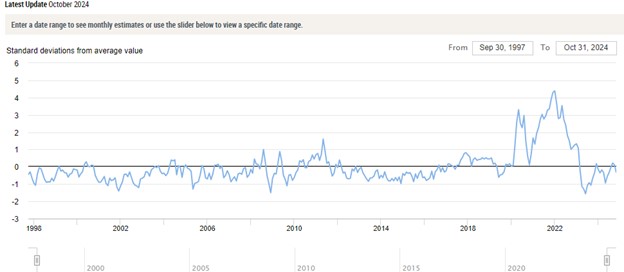

1. Supply Chain Pressures Are Easing. One key driver of recent inflation has been supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Factories shut down, transportation networks were strained, and production backlogs caused prices to spike for essential goods. But the situation is improving rapidly. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, global supply chain bottlenecks have eased and are approaching pre-pandemic levels.

This normalization is critical because it reduces production costs, directly impacting consumer prices. As the flow of goods becomes more predictable and efficient, we can expect a continued downward trend in the prices of products ranging from cars to electronics and household goods.

2. Energy Prices Are Stabilizing

Energy prices, particularly those for oil and natural gas, have been another significant factor pushing inflation higher. Spikes in energy costs can ripple through the economy, raising expenses for transportation, heating, and manufacturing. However, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), oil production has increased, and global supply levels are becoming more balanced, reducing oil prices. With energy prices stabilizing, the economy will face less inflationary pressure, and the cost of living should become more manageable.

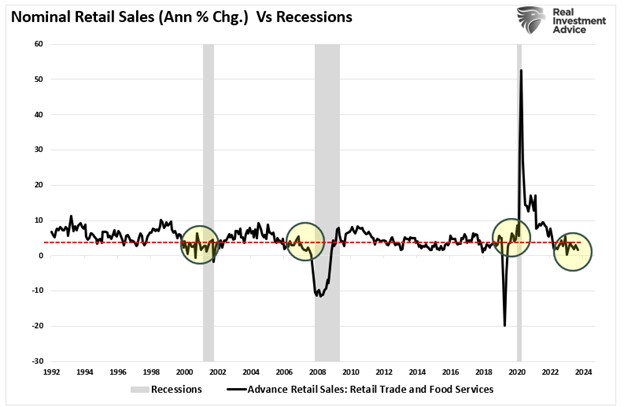

3. Changes in Consumer Spending Habits

Consumer behavior has shifted significantly since the height of the pandemic. During the early days of COVID-19, spending was heavily focused on goods like home gym equipment, furniture, and electronics. However, as the economy has reopened, consumer spending has gradually moved from goods to services, such as travel, dining, and entertainment, which have a much lower “multiplier effect,” economically speaking. This shift in spending reduces demand for durable goods, which have seen significant price increases. With demand cooling, prices for these goods are also stabilizing, contributing to overall lower inflation.

4. Slowing Global Economic Growth

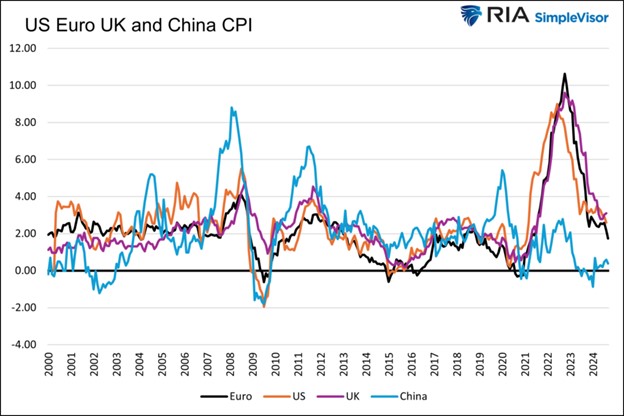

Finally, global economic conditions are crucial to the inflation outlook. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has projected a slowdown in global growth over the next year. Tighter financial conditions and geopolitical uncertainties drive that decline. A cooling global economy reduces demand for raw materials and commodities, which helps keep inflation in check. Lower import prices from trading partners can also help dampen domestic inflation. The U.S. benefits from cheaper imports if major economies like China and the European Union experience slower growth. As Michael Lebowitz recently wrote:

“Some say we will import inflation. The graph below shows inflation in the Eurozone, China, and the U.K., three of our largest trading partners. Inflation is falling alongside that of the United States. China’s inflation is near zero. Japan, not shown, has seen meager inflation with bouts of deflation for the last 25 years.”

Understanding these dynamics suggests that “Trumpflation” is likely much less of a concern than the media suggests.

Conclusion

In conclusion, concerns about “Trumpflation” are amplified by discussions of tariffs and increased government spending. However, a closer examination reveals that inflation may not rise as dramatically as feared. The normalization of supply chains, stabilizing energy prices, evolving consumer spending habits, and the backdrop of slowing global economic growth all point toward continued downward pressure on inflation. Moreover, historical evidence shows that high debt and deficits are more likely to contribute to deflation than inflation. As President Trump embarks on his second term, these factors will play a crucial role in shaping the economic outlook, likely mitigating the risk of runaway inflation and easing concerns about higher interest rates.

_______________

Lance Roberts is a Chief Portfolio Strategist/Economist for RIA Advisors. He is also the host of “The Lance Roberts Podcast” and Chief Editor of the “Real Investment Advice” website and author of “Real Investment Daily” blog and “Real Investment Report“. Follow Lance on Facebook, Twitter, Linked-In and YouTube.